The Great Funk

Falling Apart and Coming Together (on a Shag Rug)

in the Seventies

Here is a short excerpt from the book:

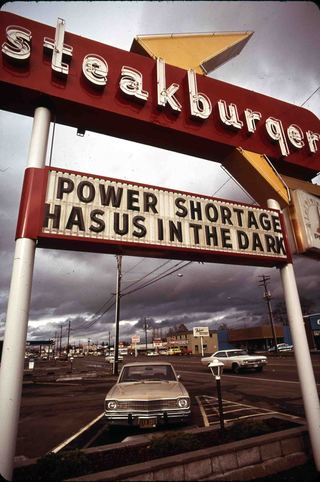

If you wanted a world that was orderly, and progress was guaranteed, the seventies were a terrible time to be alive. Cars were running out of gas. The country was running out of promise. A President was run out of office. And American troops were running out of Vietnam.

Only a decade before, as the nation anticipated the conquest of space, the defeat of poverty, an end to racism, and a society when people moved faster and felt better than they ever had before, it seemed that there was nothing America couldn’t do. Even the protestors of the Sixties objected that America was using its immense wealth and power to do the wrong things, not that it did it did things wrong. Yet, during the Seventies it seemed that the United States couldn’t do anything right. The country had fallen into the Great Funk.

By 1975, the future had turned from a promise to a shock. Following the first Arab oil embargo of 1973, the Eldorado and the dream of freedom and luxury it embodied had come to appear grotesque, a true road to ruin. Overnight, Americans went from a world where abundance was assured to one in which scarcity was an ever-looming threat, and they didn’t handle it well. Mysterious rumors of shortages of everything from toilet paper to raisins led to runs on supermarkets and hoarding as the everyday necessities of life seemed no longer to be guaranteed.

The Vietnam War had come to an ignominious end, with diplomats escaping by helicopter from the roof of the embassy in Saigon. Earlier, Richard Nixon, too, had left in a helicopter, after resigning the Presidency in the wake of a bungled burglary and a cover-up that revealed a personality even more diabolical and self-destructively insecure than even his many enemies had imagined. For nearly two years, Americans had seen the intellectually brilliant, sometimes visionary President they had re-elected in a landslide ever-so-slowly revealed as a foul-mouthed conspirator, condemned by his own words on his own secret tapes. (“NIXON BUGGED HIMSELF” screamed the New York Post headline.)

And then there was the economy, producing very little actual growth, while prices were rising at a double-digit pace. This was something that elementary economics textbooks said could not happen, and yet it did. This so-called stagflation so traumatized politicians and policy-makers that for the rest of the century, their central goal was to assure that it would not happen again. “Things can’t get any worse,” was the expert consensus in 1970, after the booming economy of the Sixties started to sputter in 1968 and inflation persisted the following year. The experts, it turned out, had no idea. You could get eight loaves of bread for a dollar at the supermarket in 1970. The next year, that dollar bought five, in 1973 four, and by the end of the decade, one and part of a second.

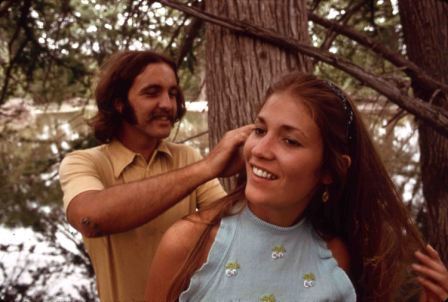

Still, after the litany of disasters and the inventory of embarrassments have been recited, many who lived through this supposed nightmare of an era recall good times, and not just hedonistic ones. The Seventies were a time when many people felt free to invent or reinvent themselves, or to feel good about who they were. In civic life, the confrontations of the Sixties gave way to improvisation and co-operation. The routines of everyday life—eating, staying comfortable, taking out the trash—could be meaningful, both personally and globally.

Some of the old promises of progress had been proven to be empty or unwise, but new possibilities were emerging. There is something deeply liberating about discovering that you don’t live in a perfect world. When what you have always been taught has been shown to be untrue, that opens the opportunity of finding new truths on your own. When things fall apart, you can put them together in new ways. When the center cannot hold, well that’s good for those out on the edge. When the forces of order are revealed to be a malign conspiracy, it’s a good time for a party.