Populuxe

Populuxe is a synthetic word, created in the spirit of the many coined words of the time. Madison Avenue kept inventing words like "autodynamic," which described a shape of car which made no sense aerodynamically. Gardol was an invisible shield that stopped bullets and hard-hit baseballs to dramatize the effectiveness of a toothpaste. It was more a metaphor than an ingredient. Slenderella was a way to lose weight, and maybe meet a prince besides. Like these synthetic words, Populuxe has readfly identifiable roots, and it reaches toward an ineffable emotion. It derives, of course, from populism and popularity, with just a fleeting allusion to pop art, which took Populuxe imagery and attitudes as subject matter. And it has luxury, popular luxury, luxury for all. This may be a contradiction in terms, but it is an expression of the spirit of the time and the rationale for many of the products that were produced. And, finally, Populuxe contains a thoroughly unnecessary "e," to give it class. That final embellishment of a practical and straightforward invention is what makes the word Populuxe, well, Populuxe.

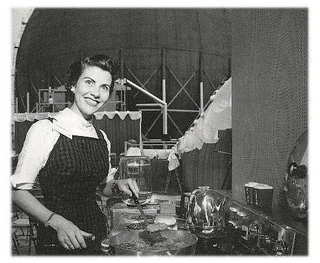

Atomburgers, coming right up!

And if her expression seems a bit manic, and hysteria seems to be leaking in around the edges, remember that the 1950s were an anxious time. Most people believed life was getting better. Average wages were rising. Average houses were getting bigger. Average families were getting larger. Yet optimism and dread can co-exist. In 1959, a poll of teenagers discovered that most young people believed that their lives would get steadily better--and that there would be a nuclear war in their lifetimes. Progress brought stress. The Populuxe era--between 1954 and 1964--was the peak of popularity for psychoanalysis, and also for martinis.

-x_small.jpg)

The Plymouth was the lowliest of the so-called "low-priced three," but by 1959, even purchasers of the cheapest car could afford to pay for extraneous, but expressive sheet metal. Advertisements for Chrysler Corporation, maker of the Plymouth, claimed that tailfins provided "stability at speed," a phrase that could have been the slogan for the entire era.

Here is a short excerpt from the first chapter:

The decade from 1954 to 1964 was one of history's great shopping sprees, as many Americans went on a baroque bender and adorned their mass-produced houses, furniture and machines with accouterments of the space ange and of the American frontier. "Live your dreams and meet your budget," one advertisement promised, and unprecedented numbers of Americans were able to do it. What they bought was rarely fine, but it was often fun. There were so many things to buy--a power lawnmower, a modern dinette set, a washer with a window through which you could see the wash water turn disgustingly gray, a family room, a charcoal grill. Products were available in a lurid rainbow of colors and a steadily changiung array of styles. Commonplace objects took extraordinary form, and the novel and exotic quickly turned commonplace.

It was, materially, a kind of gold age, but it was one that left few monuments because the pleasures of its newfound prosperity were, like Groucho Marx's secret word, "something you find around the house." There was so much wealth it did not need to be shared. Each householder was able to have his own little Versailles along a cul-de-sac. People were physically separated, out in their own in a muddy and unfinished landscape, but they were also linked as never before through advertising, television and magazines. Industry saw them as something new, "a mass market," an overwhelmingly powerful generator of profits and economic growth. There was ebullience in this grand display of appetite, a naivete that was winning, and today, touching...

The essence of Populuxe is not merely having things. It is having things in a way that they and never been had before, and it is an expression of outright, thoroughly vulgar joy in bing able to live so well. "You will have a greater chance to be yourself than any people in the history of civilization" House Beautiful told it readers in 1953. The greatness of America would be expresed by enrichment of the environment, bu the addition of new equipment to the household and by giving up European models and, instead, finding inspiration in the American past and, most of all, in its promising future.