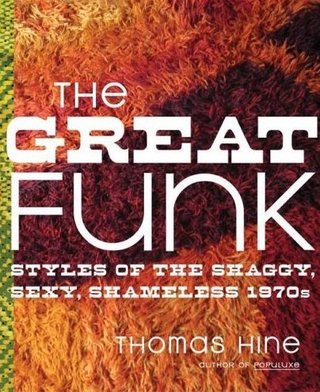

Looking at the Seventies to Understand the Even Greater Funk We're In Now.

The textured life

What we can still learn from the '70s

Thomas Hine

from the Boston Globe, April 5, 2009

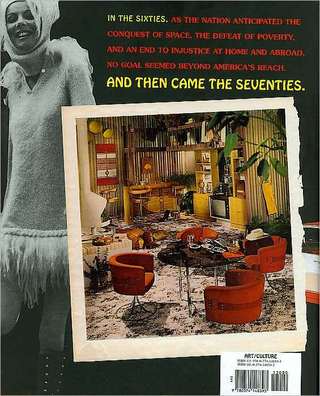

SHAG RUGS ARE back in the stores. The rooms in decorating magazines are starting to look just a little bit cluttered. Solar panels are hot. Men are wearing beards. There are orange cars on the road, something not seen since the days of the flaming Ford Pinto. For all we know, avocado-colored appliances are about to mount a comeback.

The culture seems to be having a 1970s moment.

It's true that the 1970s have been revived at regular intervals in fashion, music, and entertainment ever since they ended. But this time, the echo is different. It's not just superficial scavenging but rather a deeper reconnection. Those '70s aesthetics didn't come from nowhere: they were born from a particular kind of change and uncertainty. And in the end, they embodied an imaginative way out of the malaise of the time.

In the flush times of the early 1960s, as in the early 2000s, surfaces tended to be smooth, cool, and technological, reflecting a confidence that wars could be limited, economies could be fine-tuned, and that the best and the brightest had matters firmly in hand. In the 1970s, the world turned hairy, and our floor coverings, our clothes, and even our bodies soon followed.

The '70s were a bad time. The country experienced two oil shocks. A corrupt president and vice president were driven from office. People were so skittish that a Johnny Carson joke on "The Tonight Show" set off panic buying of toilet paper and a nationwide shortage. Cars were catching fire, and plate glass windows were falling from Boston's John Hancock Tower, producing a skyline dominated by plywood. Unemployment was high and assets were melting as prices kept rising. It was the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

The styles of the 1970s grew directly from this sense of upheaval. The symbolism of progress gave way to an aesthetic of salvage, of willfully mismatched wardrobes, of luxuriant plants and luxuriant hair. A sudden new awareness of environmental limits brought an emphasis on earth tones. And where there used to be smooth surfaces - on our floors, on our bodies, even in our food - people embraced the tactile, the textured. In a time when so many seemingly reliable institutions were failing, shag rugs, beards, and granola felt real, natural, and comforting. Even the decline and violence of the cities had an aesthetic impact; graffiti could be dispiriting yet beautiful all at once.

Now, our own smooth times are over. We have been undone by financial instruments and practices most of us still don't fully understand. Figures like Alan Greenspan, once viewed as almost infallible, admit that they did not know what was going on. Our wealth turned out to be a figment of our imagination. It's no wonder we're drawn to things that feel real, authentic, and natural.

Even before last autumn's stock market crash, symptoms of that old '70s funk were evident. Hurricane Katrina, collapsing bridges, and high gas prices helped create a general sense that America was headed in the wrong direction. Shortly after it began to be evident that the mission hadn't been accomplished in Iraq, the earth tones started to reappear. The reawakening of environmental consciousness, and especially fears of global warming, brought a revival of "green design."

Designers and manufacturers created soft and sheltering surroundings for consumers to hunker down in. They combined the trends by producing shag rugs in such environmentally conscious materials as bamboo, jute, and recycled newspapers. One carpet maker has even produced multicolored shag with a pixilated look that appeals to our increasingly digital way of seeing.

Beards began to be fuller and more numerous on the street, a phenomenon that probably signals the end of the fast-track career. A man with a beard is likely taking time, voluntarily or not, to figure out who he should become.

Despite the similarities, there are at least two things about our new funk that is very different from that of the '70s. For one thing, the economics of the downturn are almost the opposite of that of the '70s. Back then, the biggest problem was rapidly rising prices. If you had money and a job, you wanted to buy now, before prices went up. This helped train baby boomers to live on credit, and drove a new kind of consumer culture that embraced Japanese cars and microwave ovens - both of which caught on during that decade - as well as such short-lived frivolities as hot pants and Pet Rocks. Fashion went to extremes: men wore densely striped suits with flapping lapels, patterned shirts, and bib-like ties, while women bought embroidered handbags and peasant-look fashions.

Now, deflation is the threat, and many consumers may be inclined to wait and see if prices go down. If we don't go shopping, designers and merchants won't be turning out the kind of imaginative products and ideas that gave the 1970s such a distinctive, if mixed, stylistic heritage.

The other difference is that the '70s recognized the failure of its institutions and expectations far more comprehensively than we have. In effect, America declared moral and intellectual bankruptcy and reorganized - creating new zones of freedom in which people found opportunities for liberation. Punks made a style out of social collapse. Gays, old people, computer hobbyists, and evangelicals created societies of their own - and gave rise to inventions, such as the personal computer and the megachurch, that had a profound impact on contemporary life.

President Obama's oft-stated goal is to bring America together again, which means essentially to undo the shattering of the '70s and agree on some core American values. Much of the time, however, he has been advocating the bailout of systems and institutions that he acknowledges have failed. If we're in a time of transformation, we may be closer to the beginning of the crisis than the end.

The example of the 1970s suggests that times like these bring changes that can have profound effects on decades to come. The aesthetic of that time - clashing, chaotic, eclectic, and textured - still speaks vividly about the era's struggle and creative response. It remains to be seen whether we will go beyond simply reviving the looks of the '70s, and find equally compelling new ways to see, to live, and to be.

To paraphrase George Clinton, you gotta have The Great Funk.

Kirkus Reviews

About this site

If you click on the page called Works, you will find comments others have made about the books. Most of these are positive--it is my website after all, but they are also fairly interesting and give a sense of the issues the books raise. The pages linked to each work offer some short excerpts from the books, some of my comments and an illustration or two. Those pages contain links that enable you to order the books.